I once bought a city block in an older part of town to build a pocket neighborhood. The neighbors opposed my project, so I sought the advice of the area planner, who was an architectural historian. I told him I wanted to develop homes that fit in with the neighborhood; I asked him to help me design them by showing me the best examples of period affordable housing.

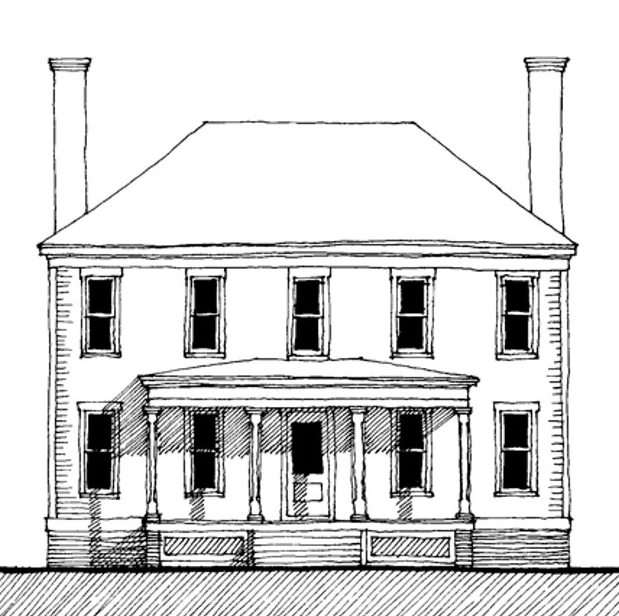

We toured the city, and he pointed out the bungalow home styles and authentic façade details that made the best postwar neighborhoods quaint, yet still economical. I snapped pictures and then huddled with my architect to reproduce those details as closely as possible by using inexpensive cladding materials, including vinyl siding. The city planners approved my development, the neighborhood (eventually) supported it, and within 12 months of breaking ground, I built, sold, and won the NAHB Workforce Housing award for 24 traditionally designed homes (Figure 1).

Since then, I have remained a traditional neighborhood developer, using the same technique: study and reproduce the best area architecture. The secret lies in knowing what to observe and how to replicate the essential elements without overspending — and I am ready to share what I have learned.

Study the block face first

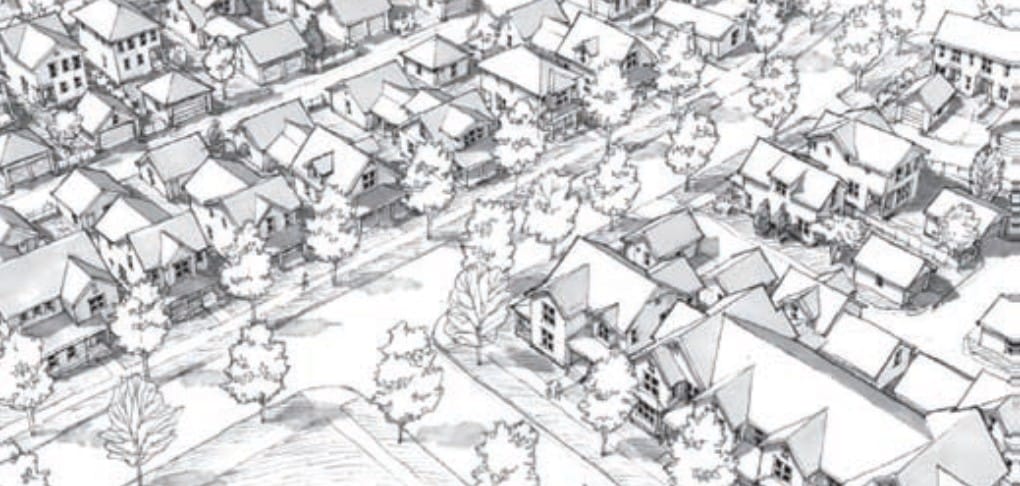

Driving around the best traditional neighborhoods in a city, notice that the homes along each block present a harmonious and consistent appearance that gives those streets local character (Figure 2). As builders, we tend to focus on the individual house. Online, home builders will often share renderings of their model homes set on a verdant lawn under a glorious sky, as if the house were in the wilderness with no neighborhood context. While some may be truly stand-alone houses, it is often not the case; the homes become victim to overdesign (think myriad elevation changes and materials) when placed in their true context (Figure 3).

Figure 2: In a traditional neighborhood, homes along the block face remain compatible, creating neighborhood appeal, vs. competing for curb appeal. The Architecture of Traditional Neighborhoods, Onaran et al 2019, courtesy authors.

Figure 3: This home, while attractive, is also hyperactive, combining three materials, Dutch lap siding, vertical siding, and masonry as if a showroom of building materials. Be careful with masonry, a heavy element that should go on the foundation, not as wainscot or up an accent wall. No traditional homes were built this way. Courtesy Vinyl Siding Institute

A block face — defined as the homes along the street — with many volumes and variations looks too busy, and busy buildings fight their context. They scream, “Hey, look at me!” There is certainly a place for fanciful homes with outlandish architecture; however, it is often not in a traditional or historical neighborhood setting (Figure 4a and 4b).

Figure 4a: Many builders design homes to stand out, featuring many elevation changes and a variety of materials. These homes work well when standing apart from their neighbors. Courtesy Steve Mouzon

Figure 4b: A traditional neighborhood home features one or two materials, and a simpler façade with classical proportions that harmonize with the street face – a case of less is more. Courtesy Steve Mouzon

One of the basic principles of traditional neighborhood development is to design the whole block face before detailing the individual houses. This approach often yields simpler façades that consider the neighborhood context and avoid the temptation of overdesigning any one of the homes (Figure 5 and 6).

Figure 5: Note the subtle variety of these traditional homes along pedestrian green space. They all feature deep porches, subtle façade variation and similar massing. Drawing from The Architecture of Traditional Neighborhoods, Onaran et al 2019, courtesy authors

Figure 6: A traditional neighborhood offers home close to the sidewalk typically on narrow lots. This arrangement makes for pleasant sidewalks with engaging architecture, subtle variety, and proximity with neighbors. Note how street trees on tree lawns and cars parked along the curb slow traffic and protect pedestrians. The essentials of traditional neighborhood development include walkability and proximity. Drawing from The Architecture of Traditional Neighborhoods, Onaran et al 2019, courtesy authors.

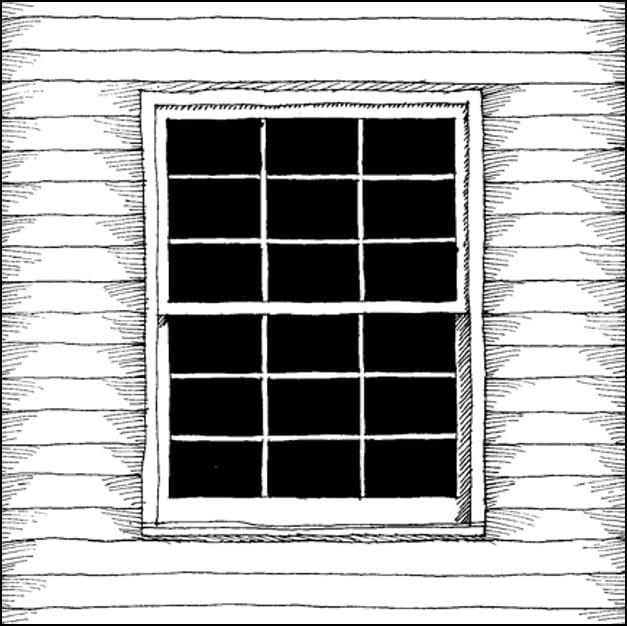

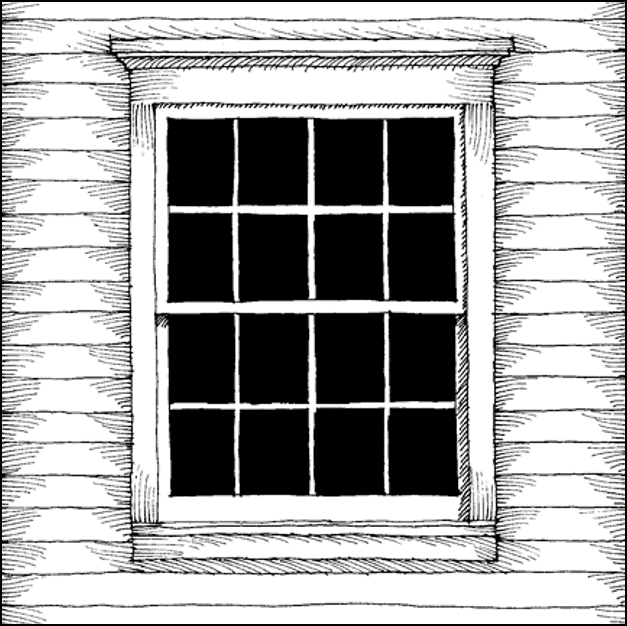

The way homes in a traditional neighborhood obtain individuality is through subtle variation in their forms and ornamentation. Notice in old communities that the building styles and shapes — what architects call massing — remain consistent (Figure 7), but the details differ. You will see porch railings of all different patterns; variations in the eaves and rake ornaments; unique window and door lintels, muntons, and mullions; changes in color. These are all examples of how to add defining elements to a façade while still fitting in with the overall neighborhood character (Figure 8).

Match the massing

The goal of traditional neighborhood architecture is harmony without monotony. Harmony is perhaps most easily defined in terms of an orchestra. All the instruments play in the same key, but not the same note; otherwise, it would likely be a very boring concert.

Harmony in housing is much the same; it can be achieved through variation within a consistent range of style. To describe what creates harmony within diversity along a block face, architects often use highfalutin-sounding terms such as “horizontality” and “verticality.” One way to think of horizontal or vertical harmony is in terms of horizontal and vertical stripes. Most people would not sport a striped shirt with checkered pants, so follow the same principle when designing the block face (Figure 9a and 9b).

Horizontality refers to styles that accentuate width, such as Prairie and Craftsman style buildings. Verticality relates to styles that accentuate height, such as Victorian, Modern and Southern styles. On a single block face, a house emphasizing horizontality, such as Prairie style, flanked between two soaring Victorian homes will look out of place. If building infill, careful attention should be given to neighboring buildings so that the new building blends in harmoniously. The idea of a traditional neighborhood is precisely neighborliness: homes that get along (Figure 10).

The devil in the detailing

In this lifetime, there are so many examples of poorly detailed buildings that some of us have become blind to the mistakes; we have forgotten what carpenters knew instinctively 100 years ago. To remedy this, look to the older parts of a town to find examples of proper architectural detailing.

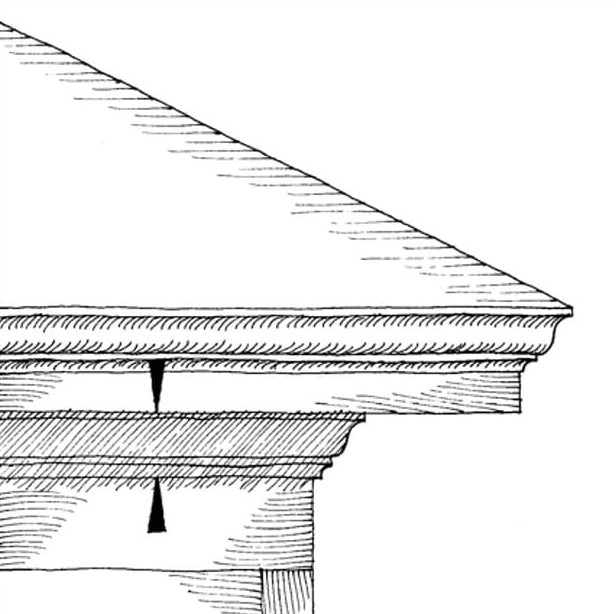

Figure 11a: This drawing illustrates a common mistake. The arrows point to a crown molding (cyma recta or cymatium) placed incorrectly as a supporting element. The name gives it away, the crown goes on the head, not under the chin. Use crown moldings to terminate a trim, on top. Courtesy Steve Mouzon

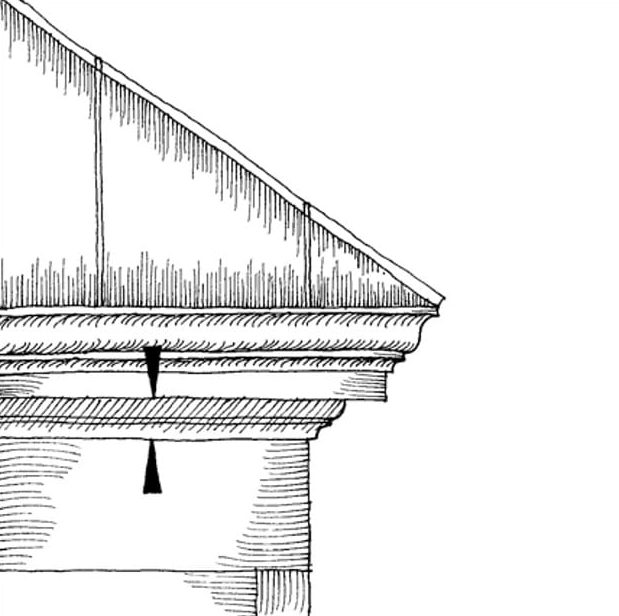

Figure 11b: This drawing illustrates the proper molding to use as a supporting element, the cyma reversa, with the convex portion at the top, like a cupped hand holding the board on top, often called the “ogee” at the lumber yard. Courtesy Steve Mouzon

Work to develop a sense of proportion and discover the original purposes for details. For example, that brick molding is for, well, brick, and not for siding. (Figure 11a). Crown molding (cyma recta) goes on top, and the ovolo (cyma reversa) goes under, as a supporting molding (Figure 11b). Shutters should shut and attach to the window jambs rather than beside the window (Figure 13a and 13b). And windows and doors have a structural frame that resembles posts and beams more than picture frames (Figure 14a, 14b, and 14c).

Figure 14a: The molding name says it all, brick molding belongs on brick, not rimmed with J-channel and the vinyl siding – a common error. Courtesy Steve Mouzon

Figure 14b: Windows frames have proportion. The sill is slim, the vertical lineals about 2/3 the width of the header, and the lintel, or header about 1/6th the width of the window opening. Now, keep in mind that traditional windows were tall and narrow – no huge widths. Courtesy Steve Mouzon

Figure 14c: A well-proportioned, double-hung window trimmed with PVC moldings. The trim has built-in J-channel, allowing the polypropylene shake surrounding the window to pocket into the trim without screaming, “I’m plastic!” Courtesy Vinyl Siding Institute

Much of the blame that cheaper materials get for looking fake comes from poor detailing rather than deficiencies in the product. An architect or builder can, however, obtain a satisfactory reproduction of most traditional construction patterns using cheaper products if they know what they’re doing. Learning how the details should go is the first step; researching products available to reproduce those details comes next.

Designing with modern materials

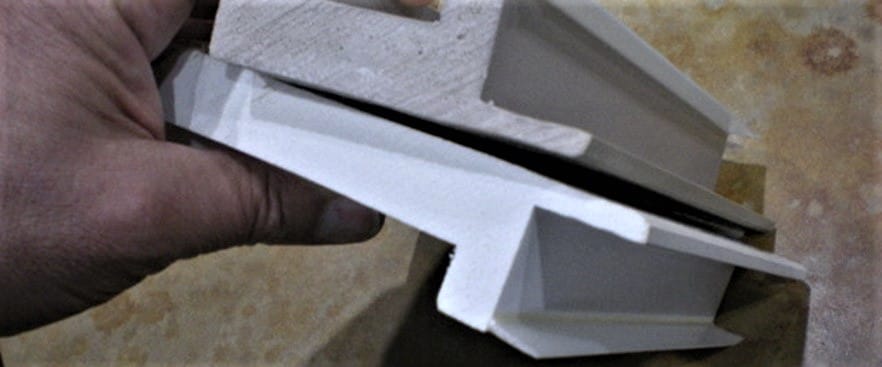

The most comprehensive selection of trim choices comes with cellular PVC moldings; they can take any shape imaginable. Major cladding manufacturers offer a full line of profiles that resemble and sometimes improve upon available wood products because they are not limited to milling patterns out of dimensional stock.

Independent providers augment the assortment of available trim, especially when it comes to lintels, casings, fluted columns, pediments, and brackets. Look online to find the options available; some are unique and others offer easy-to-install versions of complex, traditional shapes that would require master artisans to fabricate with wood (Figure 15).

When choosing products, consider their limitations. For example, most modern cladding cannot satisfactorily reproduce a mitered corner. Some polypropylene shake does a reasonable job from afar, but not up close (Figure 16). Cellular PVC shake does do an excellent job with mitered corners, but does not offer the depth of grain required for a realistic appearance.

Figure 17: Alternating the butt of the end panel courses yields a convincing mitered corner with fiber cement clapboard, once painted. Fernando Pagés Ruiz

Figure 18: Polyash siding cuts like wood, so you can obtain a true mitered corner. The material requires paint. Courtesy Vinyl Siding Institute

Fiber cement siding, with the ends alternating course to course, creates a reasonable resemblance from a few feet away (Figure 17). The new polyash (polyurethane and fly ash) siding offers the best corner because it cuts like wood and corners can be mitered. Of note, polyash siding requires painting (Figure 18).

The absence of smooth (non-textured) siding remains a sensitive topic with the manufacturers of most siding lines and explains, in part, the ascendancy of fiber cement siding that offers one smooth and one grained face; either can be specified. Pro tip: Choose the smooth. Milled wood has no grain texture unless it has rotted.

A new wood fiber line from SmartSide features smooth clapboard, and Restoration Smooth from CertainTeed offers a select line of thick, smooth vinyl siding. Unfortunately, at the time of this writing, none of these companies manufacture smooth siding in all their profiles, so you’re limited to clapboard.

Architects complain about the use of J-channel, the receiving end of siding that expands and contracts with temperature variations. The J-channel provides a slot that accommodates this movement, and a gutter to drain water around openings. However, it is also the telltale sign of artificial materials since wood does not require a J-channel. A middle-of-the-road solution comes with trims that have an integrated J-channel, avoiding the maligned trim.

Figure 19a: Although the shadow line along the edge of this window trimmed with integrated J-channel gives it away, from the front of this window, the trims will look like wood cladding butted up to wood trim. Courtesy Vinyl Siding Institute

Figure 19b: When trimming an opening, instead of using wood moldings scribed with J-channel, use PVC trims with integrated J-channel. Fernando Pagés Ruiz

Instead of using wood casing around a door or window, use a polymeric trim kit with an integrated receiver (Figure 19a and 19b). The effect is of a carpenter that slapped the trim over the siding rather than cut each plank to fit, but carpenters have done this for generations (Figure 20). If J-channel is an absolute ‘no’, fiber cement, wood fiber, and polyash products can butt up against trim and adjacent panels without a receiver.

Some cellular PVC siding profiles interlock to produce a satisfying end-butt between adjacent panels and don’t require a receiver at corners and around openings. Cellular PVC siding represents a high-end material category with elegant and highly durable product lines (Figure 21).

Quality counts

As with most products, architectural polymers come in a range of quality. Premium siding products range to a thickness of .048 inches to 0.050 inches, with builder’s grade siding at 0.040 inches to 0.045 inches. The thinner materials (0.040 inches and less) are the least costly and lowest quality. They may telegraph defects in the substructure, such as bowed framing and swollen sheathing.

The thicker and, thus, more rigid materials provide a smooth finish. Due to high flexibility and durability, they also increase life expectancy. Most polymeric manufacturers follow ASTM standards and industry certifications for durability and colorfastness. The ASTM and certification labels can be found on the packaging. In high-wind areas, confirm the wind resistance rating and follow the installation instructions carefully to ensure the siding will not blow off the house in a storm.

Because polymer products are relatively inexpensive compared to their wood counterparts, these materials have often helped developers construct low-cost structures. The association between polymeric materials and lesser architecture has prejudiced the designer’s eye. The products are not at fault; the inattention to detail, authentic design, and quality of construction are to blame.

Authentic, contextual urban architecture can be achieved by integrating innovative materials that reproduce traditional construction patterns with added durability. Builders can now combine modern technology with human-scale urban environments that please the soul, attract the eye, and stand the test of time.