Studies show the enduring and far-reaching benefits of homeownership.

By Paul Emrath

Throughout most of its 75-year history, NAHB has emphasized how effectively homeownership can helped the typical American family to accumulate wealth. As discussed in a 2006 article, a primary residence is by far the largest asset for most home owners.

Although a home is most often acquired by taking out a mortgage and accumulating debt, the historic tendency for house price appreciation to outpace general inflation (assisted by some federal tax policies, such as the mortgage interest deduction) resulted in consistent and substantial gains in wealth and home equity for U.S. home owners. Unlike other investments that can be used to grow household wealth, such as common stocks, rates of return on a primary residence tended to be much more consistent and predictable.

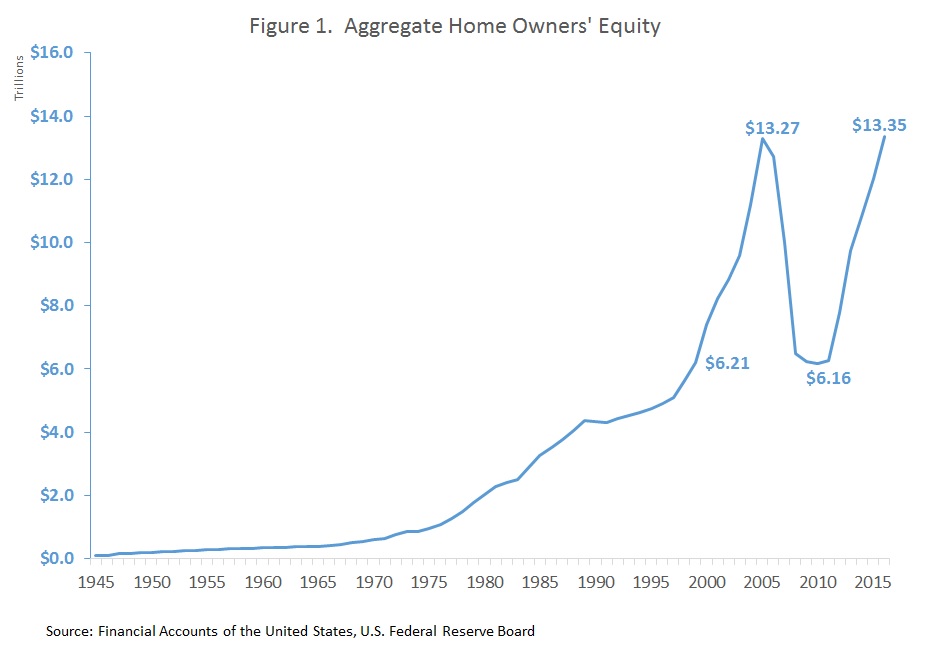

But the historic downturn that began after 2006, when house prices fell nationally in nominal, or unadjusted, terms for the first time since World War II, cast a shadow on this rosy picture. Indeed, the total amount of housing equity fell by 54 percent from its pre-recession peak to a low of $6.16 trillion in 2010 (see figure 1).

Even in 2010, however, owner-occupied homes remained a key component of household wealth in the U.S. After that, aggregate owners’ equity recovered significantly, growing by 117 percent from 2010 to 2016 — reaching $13.35 trillion, slightly above its previous peak of $13.27 trillion in nominal terms.

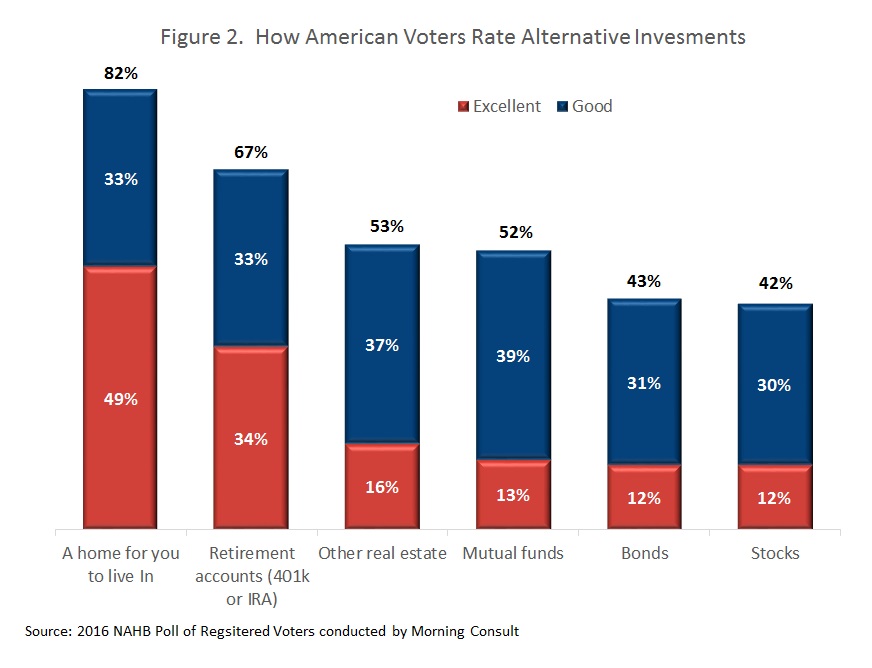

So where do we stand now? After all this turmoil, has housing’s reputation as a stable, wealth-building investment been restored by the post-2010 growth in owners’ equity? The answer appears to be yes, according to recent NAHB poll of 2,803 registered voters, conducted online by Morning Consult in July 2016.

In that survey, 82 percent of voters said owning a home was at least a good investment, and nearly half rated it as excellent, far higher than for any of the other investments listed in the survey (see figure 2).

Benefits are far-reaching

Beyond creating wealth in the form of home equity, a substantial body of research in the social science and medical fields demonstrates that owner-occupied homes can convey other benefits to their owners. For example, an article by well-known medical sociologist Sally Mcintyre and four co-authors found that home owners have better health and greater life expectancy. Another article found that owning a home reduces the probability of divorce.

A study by Richard Alba, John Logan, and Paul Bellair found that home owners were significantly less likely than renters to be crime victims in the suburbs of New York. A few years later, a study by Ed Glaeser and Bruce Sacerdote found similar results in a variety of cities.

Academic research has also investigated ways in which homeownership can benefit society at large. Indeed, such spillover benefits are often cited as a justification for the mortgage interest deduction and other polices to promote homeownership. One example is a study by Denise DiPasquale and Ed Glaeser, which found that home owners tend to have a better understanding of the political process and are more likely to vote in local elections. One of the more recent studies, by Kim Manturuk, Mark Lindblad, and Roberto Quercia, found that owning a home increases participation in neighborhood organizations, specifically in lower-income neighborhoods.

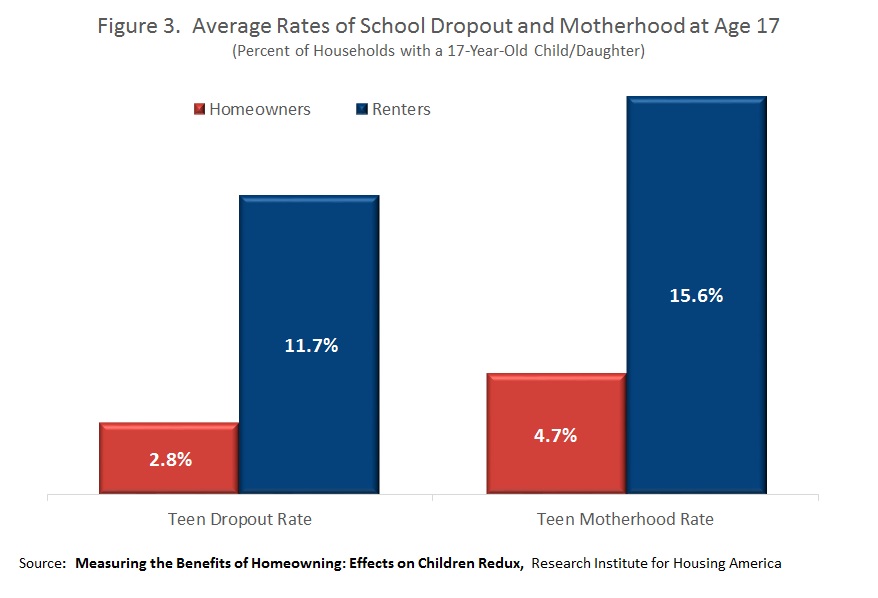

Among the potential social benefits of homeownership, impacts on children are generally seen as particularly significant. An important article by Thomas Boehma and Alan Schlottmann that tracked household members over time found that children of home owners attained higher level of education and, thereby, higher incomes later in life. An often-cited study by Richard Green and Michelle White found that children of home owners tend to stay in school longer, and daughters of home owners are less likely to become pregnant as teenagers.

Some of these articles have become a bit dated. The original Green and White study, for instance, was published in 1997. As rule, academic journals don’t publish articles that simply update previous research, no matter how influential, with newer data. But in 2012, the Mortgage Banker Association’s Research Institute for Housing America commissioned Green and White, along with Gary Painter, to revisit the 1997 study. The results confirmed their earlier findings. The updated data show that, compared to renters, teen dropout and pregnancy rates for home owners are only about one-fourth as large (see figure 3).

These studies were all written by professional academic researchers and report impacts of homeownership after statistically controlling for factors such as household income that may influence the outcome. The statistical work in the Green, Painter, and White paper is particularly robust in this regard. And in that paper, the positive effects of homeownership (shown in fig. 3) survive a battery of statistical tests as long as the home owner made at least a minimal down payment when purchasing the home.

What about renters?

Although there are advantages to owning a home, there is still an important place in the United States for apartments and other types of rental housing. As stated in a 2016 report by the National Association of Realtors, “homeownership and stable housing go hand in hand. Home owners move far less frequently than renters, and hence are embedded into the same neighborhood and community for a longer period.”

But not every household can be in a stable situation. Households anticipating a change in family or job status need the flexibility to move into a different location or type of home. Indeed, the economy needs some locational flexibility in its workforce. Transaction costs associated with buying and selling may therefore make it more practical for people at a particular stage in their lives to rent.

Also, although we might wish otherwise, not everyone can afford to own a home. For example, as described in a 2004 NAHB study, it is virtually impossible for households supported by a retail sales job to find a home they can afford in any large metro area. Yet the economy of every metro needs retail sales workers to function. According to the latest report from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 15.8 million people are currently employed in the retail trade industry. The bottom line in that the U.S. needs an adequate supply of housing of a variety of types to meet the needs of its diverse population.

—Paul Emrath is Vice President of Survey and Housing Policy Research at the National Association of Home Builders.

This article was originally published in the Best in American Living magazine 2017 fall issue.